Constructor - July/August 2015

Deep Space Fine

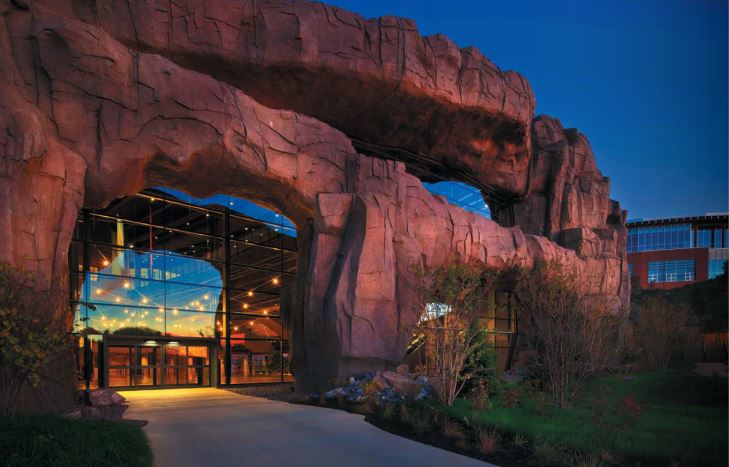

Epic Systems’ new Deep Space auditorium is spectacular to see and experience, but its constructors know it was epic collaboration and innovation that made it an Alliant Build America Grand Award winner — from the bottom up.

“It’s one thing to build a stadium,” says Jim Schumacher, Epic division manager for JP Cullen. “It’s another thing to bury it.”

He is speaking of the Epic Deep Space auditorium, the functional, beautiful engineering marvel that walked away as the 2014 Alliant Build America Grand Award winner in a year with a record number of submissions.

To say that the facility, with its stunning, cave-like façade, blends with the landscape is almost too conservative; rolling acres of green roofing, from nearly every angle, create a visual fusion of earth and architecture — one that was delivered on budget and even more miraculously: ahead of schedule.

The collaborative tack — between the construction pros at JP Cullen, the structural engineering giants at Thornton Tomasetti, architectural artisans at Cuningham, a host of major subs and the owners themselves — was the factor that pulled the great ideas together, taking the project from a literal hole in the ground to two AGC Alliant Build nods, including top honors in the winners’ circle.

Double trouble

Indeed, the project doubled from inception to final plans.

Early on-paper plans called for 405,000 square feet. That became 832,000. Twelve escalators became 42. A 45-foot-high concrete retaining wall became a 65-foot soil-nailed wall. And these are just a few examples of its exponential growth — all in the face of an immoveable delivery date. They had 28 months to occupancy, 40 overall.

Epic needed the space to be fully functional in time for its annual Users Group Meeting; there wasn’t a facility in the state that could handle the roughly 10,000 expected attendees.

So how do you put a state-of-the-art, 11,400-seat auditorium, not to mention conference rooms, training rooms and offices — collectively named “Deep Space” — 73 feet down into the unforgiving stone of Wisconsin? With “big bangs,” of course — a minimum of two daily.

“At such an aggressive pace, the work was choreographed so that activities were concurrent,” says JP Cullen division manager Dan Swanson, an executive project manager on this build. Blasting and excavation for 495,000 cubic yards of rock plus piles and concrete work were performed amid a host of other on-site work.

“At least twice per day, the horn sounded, every worker cleared the hole, a monitored blast took place and construction resumed,” Swanson explains. “This became a routine and worked without complaint or lost productivity.”

Or incidents. The 40-month undertaking utilized 293 tons of explosives on 688 blasts. Neither these nor any other elements of the project spiked safety-related incidents, which clocked in below Wisconsin averages.

Surface tension

The most user-friendly stadiums need roofs, of course; creating a massive lid to cover the space would have been daunting in any case. This one needed to support more weight than most. “Deciding to bury the project meant we would have a roof that a lot of people could walk on,” notes Swanson. “It had to be designed for assembly loading — a whole bunch of people packed on it, a soil load for grass, landscaping, walkways — making the 285-foot clear span in the auditorium particularly problematic.”

“There were technical challenges on the long-stand roof, much of which had to do with the heavy loading,” says Robert M. Stadler, P.E., S.E., vice president at Thornton Tomasetti. The movements that happen on a long-standing roof are not insignificant; the soil load alone here was massive ….”

A roof area just above the stage itself presented some very unique moveable connections in the transfer and radial trusses beneath. “There were very unique details that interfaced there,” he notes, “employing pins and linkages, thinking that is more common on large or moveable bridges, but unusual on a building structure ….”

Challenging, yes. But a source of great enjoyment for his team.

“We’re engineers! We like solving problems and enjoy digging in and figuring out the best way to proceed; it was a fun and exciting project to be a part of.”

Thornton Tomasetti, says Swanson, helped the Cullen team better understand their options, which ultimately led to the strand jacking of the auditorium’s roof system and a massive uptick in the efficiency of the process.

“We were only using a small part of the power of the 20 planned strand jacks,” Swanson explains. Their partners at TT explained they could actually lift much, much more. “And then the floodgates of creativity opened up!” The team developed a plan to pack every part and piece of the building they could into one massive lift.

“It was where the light went on and we began thinking way outside the box,” Swanson says. “Trusses were completed south to north, followed by catwalks, mechanical and electrical work, equipment supports and even winter work enclosures,” he ticks off. “We looked at it ‘upside down.’ Everything we put in the ceiling of the auditorium, normally done from underneath with lifts where the highest stuff goes in first and you work your way down — was flipped.”

Instead, the lowest elements went in first — and once through, they lifted more than 8 million pounds up into the air.

“It was just …” Swanson trails off, still wondrous, “… a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Coordinating the octopus

Micromanagement on a project of this scope and schedule would have been a death knell.

“You don’t build 852,000 square feet,” Schumacher explains, “you build eight 100,000-square-foot structures — pieces and parts that people can handle.” Along with that, he says, “comes ingenuity, brainstorming, ideas ….”

And eight separate arms — each with its own management team, subprojects working in conjunction with an overall master schedule.

“This,” says Swanson, “allowed teams to manage their schedules individually while also allowing combined schedule review in a biweekly master scheduling meeting. New continuous planning methods were developed, so that a hiccup for one area could become an opportunity for another.”

Much of the project was prefabricated off-site, then assembled and lowered into the building before the big roof lift.

“You can’t put 42 escalators in in a week,” Schumacher notes. The prefab method was an epic time-saver, shortening the installation time in the field from 24 weeks down to nine. Fifteen weeks earlier to ensure that the roof made it up, 15 weeks earlier so the sides of the building could be installed and so forth.

From procurement challenges (much of the necessary material had to come in from Belgium in a very short time) to the extensive simulation necessary to determine the number of escalators necessary to safely and efficiently move guests out from the auditorium in 20 minutes or less, each hurdle was soared over, say all three, due to the collaborative nature of the project. Technology played no small role.

“Shop drawing in the cloud was new to everyone,” says Schumacher. “Were there a few small hiccups? Yes.” Even so, he jokes that without their tech-based leap of faith they’d never have gotten it done on time. “That’s facetious,” he says.

“I don’t think it is,” Swanson counters with good humor, saying it could easily have taken a year longer.

He committed to Schumacher in February 2014 that the project would take home the Alliant Build Grand, though the project wouldn’t close up until August. Other people weren’t so quick to voice confidence aloud. This wouldn’t be its first submission; Cullen had been the bridesmaid before — but never the bride.

“There was so much innovation here, so much excellence in project management and teamwork between the owner, the designer, the construction manager and the contractor team. I’ve never been on a job with this level of cooperation and constant, direct input from the owner. It was true collaboration and true, integrative design from the beginning.”

The scale, the speed, the design — all these factors, says Stadler, make Epic’s Deep Space one of those special, career-milestone projects. His team saw it very early on.

“We knew that this was an opportunity to be a part of something iconic. We knew the owner. [Epic] had a proven track record of great design on its campus, great structures that were not plain, cookie-cutter-type buildings. We didn’t know exactly what it was going to be early on. We just knew that it was going to be something spectacular.”

Photo courtesy of JP Cullen